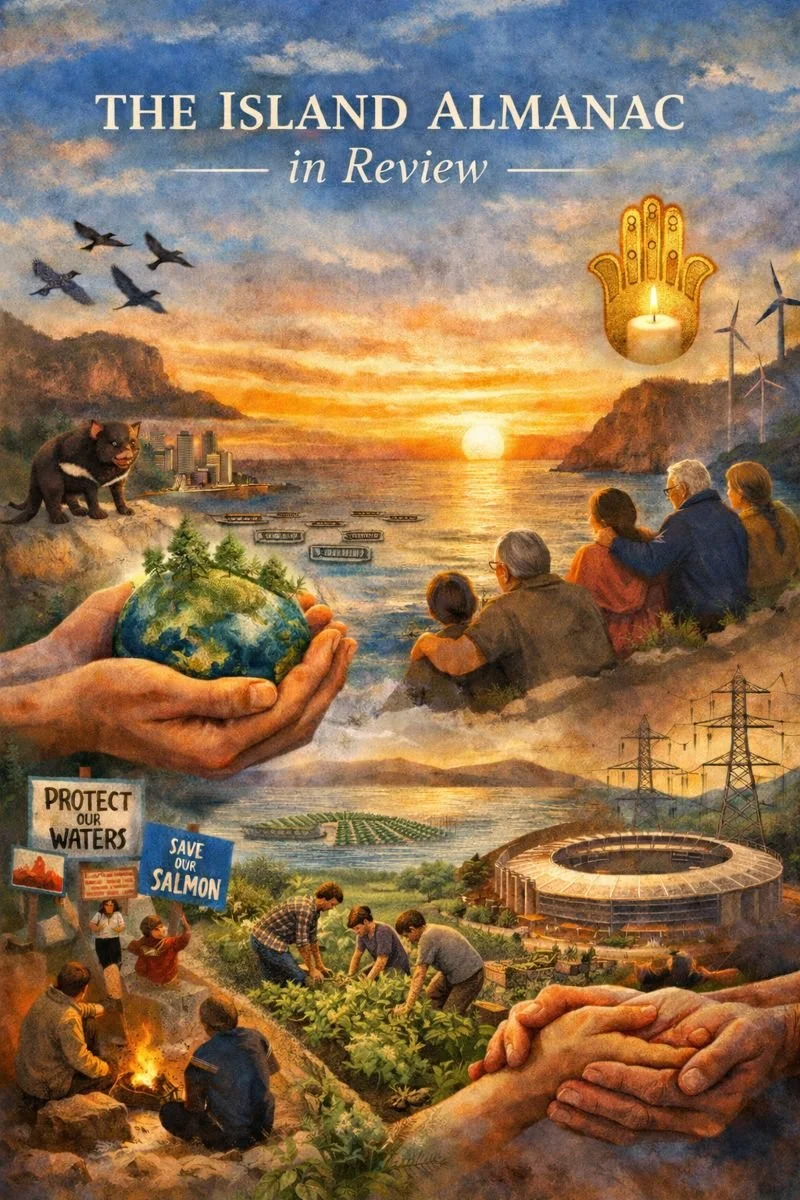

A Year of Reweaving: Notes from The Island Almanac, 2025

This year, The Island Almanac started feeling more like a living instrument I kept returning to in order to sense what was really happening beneath the headlines, beneath the daily churn of announcements and outrage, beneath the hardening of positions that so often passes for public life in Tasmania, Australia, globally and beneath the fatigue that settles in when people can feel that something is wrong but cannot quite locate where to place their hands, their hearts, or their hopes.

If I had to name the atmosphere of 2025 in one phrase, I would call it a year of heightened pressure and thinning trust, a year where big decisions arrived with the momentum of inevitability, stadium, energy infrastructure, industrial scale “solutions,” risk managed by paperwork and yet everyday life kept whispering an older truth that governments and markets still struggle to understand: that the health of a place is not secured by a single project, a single policy, or a single “win,” but by the layered, relational, quietly maintained capacities of community, ecology, and meaning, the kinds of capacities that are easiest to overlook precisely because they are ordinary and shared.

“There were moments this year when grief moved through the public body with such force that it became impossible to keep pretending we are simply dealing with “issues,” because what we are actually dealing with, again and again are ruptures in our collective sense-making, ruptures in our shared capacity to be human in the presence of pain without immediately converting pain into blame, certainty, polarity, and the old reflex to divide the world into enemies and allies.”

I wrote into that field to keep making a different kind of invitation: an invitation to return to the slow intelligence of place, the soft but disciplined work of reweaving, the steady rebuilding of what I keep calling the village layer of life, because without that layer, without the commons of attention, the commons of care, the commons of practical skill our policies become paper, our debates become theatre, our social media posts become spectacle and our nervous systems become the true governors of our decisions.

Year in Review, The Island Almanac

The rupture is real, but the binary reflex is not inevitable

In the wake of events like the Bondi tragedy, and in the long, grinding stress that many families are living through cost pressure, loneliness, the quiet despair that can sit behind a functioning face the temptation is always to collapse into the most available narrative, which is often a narrative of fear, or punishment, or “someone must be at fault,” or “this proves the other side is dangerous,” because the binary story is fast, emotionally satisfying, and culturally rewarded.

But I kept trying to write from a different place, a place I named in the Omoiyari piece the practice of holding one another with care even when we are afraid, even when we are angry, even when the world has given us a legitimate reason to grieve because if we cannot hold grief without hardening, then grief becomes fuel for the very systems that profit from our division, our consumption, our reactivity, and our need to belong to a side.

The deeper question, the one that repeats across every “issue” of our moment, is not only what happened or who decides, but what kind of people are we becoming in response, and whether we are willing to practice a form of civic maturity that can metabolise conflict and pain into learning, repair, and better design, rather than recycling the same old emotional economy of outrage and extraction.

Ecological Mind Activism: from performance to competence, from resistance to replacement

One of the major threads across the Almanac this year was my insistence that activism, as a culture, must keep evolving, because the problems we face are not just “bad decisions” that can be reversed by louder protest, but systemic patterns that reproduce themselves through supply chains, incentives, addictions, convenience, and the basic architecture of modern life.

When I wrote about Ecological Mind Activism, I was naming a shift from activism as constant alarm to activism as ecological intelligence, where we measure our effectiveness not only by what we oppose, but by what we can grow, by how many real alternatives we can build, how many people can participate, how many practices are replicable, and how much everyday life becomes less dependent on the extraction it claims to reject.

“Ecological intelligence is pluralism in practice: it trades purity for participation, and ideology for relationship, because only diverse communities can generate resilient futures.”

The salmon antibiotics story sharpened this for me, not because it is a single controversy, but because it is a near-perfect mirror of the wider pattern: industrial fragility meets ecological limits, urgency demands a technical fix, institutions scramble to manage risk and public trust, communities polarise into camps, and meanwhile the deeper question is how do we build food systems that do not require ecological compromise as the cost of business-as-usual? This question remains under-addressed because it requires a different kind of work, a work that is slow, local, relational, and deeply practical.

Ecological mind activism is the activism that can walk out of the comment thread and into the compost, out of the binary and into the kitchen, out of the endless critique and into the shared experiment, because it knows that culture is not changed primarily by argument, but by taking part in repeated experiences of another way being possible, experiences that make people less afraid, more capable, and more willing to cooperate.

Megaproject Tasmania: the stadium, Marinus, and the struggle over imagination

The stadium decision was never just about a stadium, and Marinus was never just about a cable, because megaprojects are always also stories about who counts, what progress means, and how the future is allocated, and those stories tend to arrive with a language that flattens nuance economic benefit, jobs, growth, competitiveness, “once in a generation,” “world class” even as everyday people are asking a different set of questions: What will we lose? Who carries the risk? Where is the dignity? Where is the care? Where is the accountability? Where is the evidence that this investment will regenerate rather than extract?

In my writing on the stadium, I tried to do something that our public culture rarely rewards: I tried to step out of the performative “for/against” posture and move into the more difficult terrain of scenario-making, where we actually have to describe what we would do instead, how it would work, what it would cost, what it would create, and how it would distribute benefit in ways that leave a community stronger rather than merely busier.

“The problem with megaproject culture is not only the project itself, but the way it trains a society to believe that change arrives only through large, centralised interventions, while the quieter infrastructures of community life, housing, food security, local livelihoods, youth wellbeing, mental health, place-based culture, shared spaces, conflict mediation, land stewardship, are left to “the market,” to volunteers, or to brittle, underfunded services.”

And Marinus, too, sits inside this same field, because whether one supports the link, opposes it, or remains uncertain, the deeper matter is how Tasmania understands its role, its sovereignty, its ecological limits, and its capacity to shape energy futures that are not simply engineered through communities, but designed with communities, with ethics, with transparency, with real consent, and with an honest accounting of what becomes possible when we invest in distributed resilience rather than centralised extraction dressed up as green transition.

Convivial Governance: stop funding PDFs, start funding patterns

If I had to pick one argument that I returned to repeatedly this year, it is the argument that we have confused documentation with change, and that we are living inside a culture that keeps producing strategies, frameworks, roadmaps, and consultation summaries, while failing to fund the repeatable patterns of practice that actually generate capacity on the ground.

When I wrote Stop Funding PDFs. Start Funding Patterns., I was trying to speak directly to that frustration that so many people carry this feeling that we are surrounded by plans and yet starved of tangible progress because progress, in a living systems sense, is not a line on a graph, but the spreading of healthy patterns through a community: shared work, shared learning, shared kitchens, local procurement, cooperative ownership, neighbourhood preparedness, conflict-skilled facilitation, soil literacy, youth belonging, and councils that understand their role not as mere compliance machines but as stewards of civic metabolism.

Convivial governance is what happens when a region starts designing itself as a living organism rather than a collection of departments; it is what happens when we stop asking only “what is the policy” and start asking “what is the practice, who hosts it, how often does it repeat, what does it grow, and how do we know it’s working.”

The “Third” as a civic technology: beyond binaries, into repair

A thread that sits underneath almost every Almanac piece this year is what I sometimes call the Third, the refusal to collapse into binary thinking, not because we don’t care, not because we’re trying to be neutral, but because binary culture is a low-resolution form of perception, and low-resolution perception produces low-resolution solutions.

“The Third is a civic technology, a social art, and a spiritual discipline all at once, because it requires us to be able to hold complexity without panicking, to hold conflict without demonising, to hold grief without hardening, and to hold difference without insisting that the only way to belong is to share a single position.”

This matters because many of our “issues” are now shaped less by the facts themselves and more by the emotional and narrative ecosystems that surround them, ecosystems that reward outrage, simplicity, and certainty, and punish nuance, humility, repair, and slowness, even though repair and slowness are precisely what living systems require when they are under stress.

If there is a new narrative I am trying to seed through this work, it is a narrative that re-educates the public imagination toward relational intelligence, so that we stop mistaking polarity for clarity, and start recognising that the real work of democracy is not only voting and arguing, but building the shared containers that make it possible to live together well.

The mental health crisis is not only clinical; it is cultural, economic, and relational

Mental health kept hovering at the edge of everything I wrote this year, even when it wasn’t named directly, because what I see around me—what many of us see is a growing mismatch between the human need for belonging, meaning, time, dignity, and community, and the social conditions we have normalised: speed, competition, isolation, financial stress, digital overexposure, diminished local culture, and a governance environment that can feel abstract, impersonal, and unresponsive.

It is not that therapy and clinical care are unimportant, they are essential and yet it is also true that we cannot therapise our way out of a civilisation that is systematically stripping people of the conditions that make mental health possible in the first place.

“Mental health is not only an individual attribute, it is a social ecology, and when the village layer collapses, the burden is pushed onto individuals, families, clinicians, and emergency services to carry what should be carried by community.”

So the Almanac kept returning, insistently, to village-making, to conviviality, to shared ritual, to practical skill, to food culture, to local economies, to the sacred dimension of activism, and to the simple truth that people heal faster and more gently when they are not alone.

So what did I learn, and what am I asking for next?

I learned that the headlines are real, and the consequences are real, and the stakes are real, but that the most decisive battleground is not the comment section or the parliamentary chamber, because the most decisive battleground is the cultural imagination that decides what we think is possible, what we think is normal, what we think we deserve, and what we are willing to practice together.

And I am asking for a shift that feels both radical and obvious: that we stop trying to “win” the future through argument alone, and start growing the future through capacity. Capacity is what holds grief without hatred, capacity is what holds conflict without fracture, capacity is what turns anxiety into action, and capacity is what makes the ecological mind, heart and hands more than a beautiful idea.

“If The Island Almanac has one purpose, it is to keep offering language, images, scenarios, and practices that help us remember that the future is not something that happens to us, or something that is delivered by megaprojects, or something that arrives with a press release, but something we practice into existence: meal by meal, meeting by meeting, compost pile by compost pile, council motion by council motion, neighbourly repair by neighbourly repair, until the patterns of life we long for become ordinary again.”

With love and Con Viv,

Emily / Dr Demeter

Photography at Magical Farm Tasmania by Ness Vandebourgh Photography